In recent months I have seen a marked rise in the number of people coming to me in desperation to assist their hypermobile children. These children are presenting with high levels of pain in feet, spine or knees, such that by the age of 12 -15 their ability to perform daily activities comfortably is significantly impaired.

Once diagnosed these families are being given exercises that are either: impractical, impossible for the child to do correctly or are inefficient at creating quick change so the children lose heart and a battle commences between parent (desperate to help their child) and the child (tired, in pain and fed up).

So what is hypermobility and how can you help your child? Also, this information is equally relevant to adults with this condition as well.

Hypermobility is a condition of the connective tissue of the body. In lay-mans terms, connective tissue is like a cushion’s covering – over everything in the body. Or you could describe it as a web that spreads everywhere, over bone, organs, muscles and even the heart. It has many names which depend on where it is and what it is doing. It can be called fascia, ligaments, tendons, periosteum (covering bone) pericardium (covering heart) peritoneum (covering organs) etc etc. Depending on the severity of the hypermobility syndrome the child has, different areas may be affected. So, symptoms can really vary –

· Joint instability causing frequent sprains, tendinitis or bursitis when doing activities that would not affect others.

· Joint pain

· Early-onset osteoarthritis (as early as during teen years)

· Subluxations (semi-dislocations) or full dislocations, especially in the shoulder (severe limits on one’s ability to push, pull, grasp, finger, reach, etc. or kneecaps.

· Knee pain and swelling

· Fatigue, even after short periods of exercise

· Back pain, prolapsed discs or spondylolisthesis

· Joints that make clicking noises (not always, but sometimes also a symptom of osteoarthritis)

· Susceptibility to whiplash (think bumper cars at fairgrounds)

· Temporomandibular dysfunction also known as TMD.

· Increased nerve compression disorders (such as carpal tunnel syndrome – i.e., painful wrists)

· The ability of finger locking

· Poor response to pain medication

· “Growing pains” as described in children in late afternoon or night

So you can see, this is not a “one size fits all” syndrome so the solution will never be “just do these exercises…”.

The above list is the after-effects of loose connective tissue that is not being supported by other means. But loose connective tissue has four main effects that CAN be helped with specific techniques.

1) Fatigue. Muscle pulls on tendon which pulls on bone. Ligaments hold bone to bone.

Quick exercise: Your child represents the muscle. A short therapy band represents the tendon in a person with NO hypermobility. You hold the other end, you represent the bone to be moved. Your child (the muscle) pulls the (short) band to move you (the bone). As the band is short not much effort will be required to make you move.

Repeat the exercise with a very long theraband. Now the child (the muscle) will have to work much much harder to have an effect on you (the bone). Hence the fatigue. Hence why a hypermobile child needs much stronger muscles to compensate for the longer/looser tendons and ligaments.

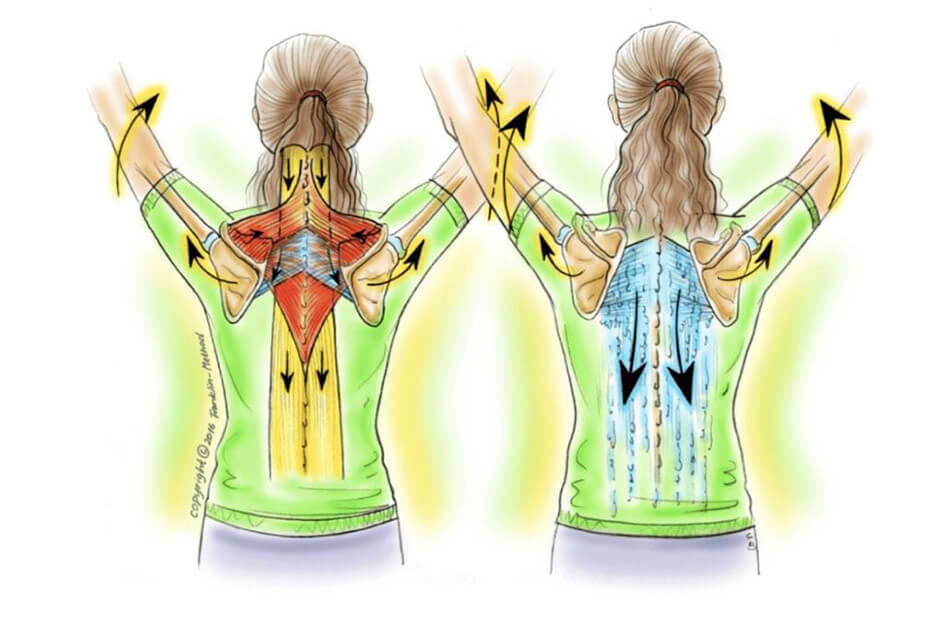

2) Joint Incongruity. This means the lack of ability to hold a joint in place as it moves. Ligaments (connective tissue that goes from bone to bone, does this.). In one foot, for example, you have 33 ligaments! If your ligaments are looser the bones may move more relative to each other. So, although (for example) you look from the outside to be flexing your hip, in fact you may well be achieving the movement through overusing one muscle and underusing another, or in some cases using a different joint altogether (for example in the spine instead) so the hip joint becomes imbalanced or stiffer and the other joints not designed to do the job become overused and that is why you get swelling, pain and wear and tear (osteoarthritis). Hypermobile people will become adept at managing to look like they are moving well but in fact they are masking their inefficient joint movements brilliantly. This can lead to increased stiffness in some joints (often hips) and increased vulnerability in other joints (often knees or spine).

3) Increased range of motion at a joint. Ligaments go from bone to bone and their length helps determine the amount of movement available at a joint. They have sensory detectors in them to send the brain a message to say if a joint has reached its happy end range. If your ligaments are longer, the range may well be much bigger and the message to your brain that you have reached the end of your designed range (from the bone’s perspective) may be faint or non-existent.

This is not all negative, it is what makes hypermobile people excellent dancers and sportspeople. In fact, this aspect of joint flexibility can be used to great advantage (if the joint is supported well enough). Michael Phelps (the American swimmer with 28 Olympic medals) is a perfect example – he is hypermobile at the shoulders which allows him an amazing range of motion and he has the strength in his muscles to support it.

4) And lastly there is lack of proprioception. Proprioception is the brain’s understanding of where the body is in space. Again, in very simple terms, inside the connective tissue are sensory organs and they give the brain feedback so it knows for example where the arm is. It can then judge how fast, far and how to move the arm in the most efficient and comfortable way. Often as hypermobile children get tired, they become even more “clumsy” as their proprioception gets worse throughout the day.

So any training we give a hypermobile person has to give them the tools they are lacking back again BEFORE they move. This means if you are asking them to do an exercise to strengthen a particular muscle it is no good showing them an exercise and asking them to copy it. They will just move as they always move, yanking their poor bodies into the position, masking the joint incongruity and strain and making it look good on the outside whilst making matters worse on the inside.

Any training for hypermobility has to use 4 elements, one for each of the problems.

1) The child must UNDERSTAND which muscle they are meant to be using. (This targets the brain which is where all movement begins!) imagery can be very helpful here to simplify things – or anatomical imagery where you can show how the muscle or joint they are moving is designed to move. By working with imagery that is in line with the body’s design they can often move more comfortably. I often find that children are talked over by practitioners who only address the parents. Kids brains are perfectly capable of understanding what is happening if it is explained in an age-appropriate way. I feel that this is absolutely key to them owning their own bodies – gaining control for themselves.

2) The child must FEEL the area that is meant to be moving (for this we use touch – tapping, brushing, squeezing themselves and props – balls, bands etc) after all, how can you move well if you don’t know what you are moving?

3) The Child must MOVE FROM THE RIGHT PLACE (this needs careful monitoring by someone who knows what to look for – until the child understands themselves how to do it). If we want a particular joint to move, it is usually comprised of two bones. We can get one bone moving in one direction – using touch and props – and the other bone moving the opposite way (counterrotation) using touch and props. Then we can be sure that movement is happening in the joint we want. For younger children or those with less ability to concentrate, using balance props can be very effective – the joints need to be aligned for balance to occur and the child’s brain will have to work out how again, though this has to be used carefully as if the joints are too misaligned this approach could backfire.

4) And lastly BOUNDARIES must be put in place so the child cannot accidently overstrain a joint before they understand what those boundaries are. Often this can be as simple as showing them how big or far a movement is allowed to be taken. We get better at what we do everyday, so practicing safe ranges of movement can then become second nature over time and as the muscle strength at the joint improves then so can the range of movement be extended (again see Michael Phelps).

Unfortunately we have one more added complication, and that is that children grow. And as they grow, the bones tend to grow first with a slight delay while the muscles catch up. It is often at this point that hypermobile children start to hit problems – such as subluxations etc.

One of the best ways to deal with this is for families to watch their children’s growth carefully and support vulnerable joints either with taping or support bandages whilst the growth spurt occurs and whilst the muscles are targeted with strength exercises to get them to strengthen up fast. This also means it is an on-going journey through their growing years and what may work brilliantly at first may have to be modified at each growth spurt. I think of it a bit like climbing up a spiral – you are always going up, but you cross over paths you were on before as you continue on your way.

Of course, all this takes patience, it involves working with the individual child and their personal version of this condition and most importantly it involves taking time to work out what unhelpful movement habits the child is using and involves unpicking them and rebuilding new habits that serve the true function of each joint in a way that the child understands so can replicate all day every day.

However, it does work – this is a testimonial from one of my clients: “Before we started working with Jessie we were at our wits’ end. My 11 year-old daughter was experiencing debilitating pain in her feet. We had seen specialist consultants, podiatrists and physiotherapists, had MRIs and dynamic ultrasounds, with the diagnosis that she has hypermobility but no way forward for any treatment to help. It got to the stage where she needed crutches most days and a wheelchair for her school trip and could not do any PE, swimming or running around at breaktime.

Jessie spent time really studying and understanding our daughter’s movements – both her feet and all the interrelated bones and ligaments. She came up with a set of exercises that she was actually able to do (she couldn’t do anything using her feet due to the pain) and the transformation has been incredible. At the end of the Easter term she was in a wheelchair. At the end of the summer term she won the long distance running athletics event. Her happiness – and ours – at being able to run around again, walk to school, swim and play is all down to Jessie. I can’t recommend her highly enough.”

I should stress that since this testimonial this brave girl had a growth spurt and the foot pain returned. The exercises that worked before were not working – on analysis, it was because the growth had occurred this time at the pelvis and hips so it was there that we needed to focus, in a slightly different way. We did and happily the pain was resolved within two weeks. The family is now attempting to monitor growth spurts more carefully with the intention of putting in place new movement habits before or at the point where they are needed – but be aware that is a tough one to judge and as a mother of a hypermobile child myself it is not always possible!

I also work with Hypermobile adults (sometimes the parents of the Hypermobile kids!) and obviously without growth spurts things should be easier, what gets in the way here is the ability of the adult to unpick habits that have become deeply ingrained through time – hard work, but not impossible.

So, if you find anything in the blog of interest and would like to discuss your child’s or your hypermobility issues, I would be happy to chat – use the contact page to get in touch.